Last updated on April 21, 2023

This post first appeared on Totally Filmi on April 20, 2020

I probably should clarify that by 420, I’m referring not to that section of the Indian penal code that gave inspiration to Raj Kapoor’s film Shri 420 (the 420 referring to someone who is a con artist or fraudster), but to 420 day, a day often given over to protests and gatherings devoted to the legalization of cannabis.

I should also note, at this point, that I live in Canada, where medical cannabis has been permitted and regulated since 2001, and where recreational cannabis use has been legal since October 2018. I recognize that this isn’t the case elsewhere, and that cannabis use can be a thorny can of worms where it isn’t.

All that said, I still couldn’t resist pulling together a 420 movie double bill. There are references to marijuana use strewn throughout Malayalam cinema – one of the more recent references is in the Malayalam film Aadu, where the local weed of choice is Idukki Gold, which is, as one of the characters notes, the only way for a Malayalam director to start his day (along with a DVD of a Korean movie for inspiration). But there are two films, both from 2013, in which marijuana use is central to the plot.

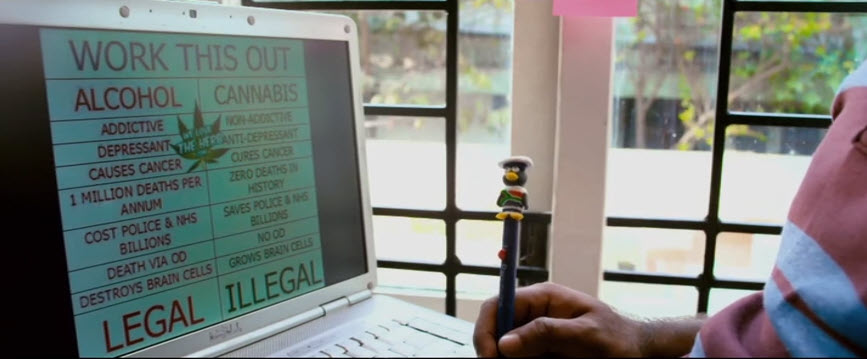

Kili Poyi tucks away a little message that many who argue for legalization will be familiar with.

The first of these is Kili Poyi (“Going Crazy”), billed as being India’s first stoner film (that is, a film in which cannabis use and cannabis culture are central to the film’s story). Chacko (Asif Ali) and Hari (Aju Varghese) work for an ad agency in Bangalore — though perhaps I should have written “work”, because Chacko and Hari spend most of their time being chewed out by their boss (Sandra Thomas) because they actually do very little work, spending most of their time chasing women, or smoking weed. In one cannabis-infused haze, they decide they need a break and book tickets to Manali (telling the boss that Hari has pneumonia, and Chacko needs to look after him). When they miss their flight — because Chacko desperately needed a toke before getting on it, and mistakenly gave the joint to their driver (don’t toke and drive, folks!) who ended up weeping over his steering wheel and unable to drive (don’t toke and drive!) – the pair borrow a car from a friend and head off to Goa.

In Goa, they continue their toking, women-chasing habits, and in the flurry of needing to escape from a gang of guys ready to beat them up, they take off in their car – which just happens to have the bag the woman Chacko was with was carrying. That bag – seen in earlier scenes – has the face of Robert DeNiro on it, his character Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver, making it easy for us to follow the bag as it travels from hand to hand. Chacko and Hari return the car, not realizing the bag is in it. Their friend, Jo, returns the bag, and the two realize, when they open it, that the bag is filled with cocaine. The rest of the film traces their attempts first to just rid themselves of the bag, and when they can’t, to sell the cocaine to get some money out of it. All the while, the actual owners of the bag are trying to track it down.

Kili Poyi is not a film for everyone. Its humour is often crass and sometimes raunchy, and there are times when I wonder if it would be better watched, as befits a stoner film, under the influence. I know if I tried that, I’d end up like Chacko and Hari’s airport driver, weeping over my metaphorical steering wheel (don’t toke and drive!). But there are some very funny moments (mostly when Chacko and Hari try to rid themselves of the bag), and in typical New Gen fashion, the film reveals its inspirations in classic films both Western and Malayalam. The film opens with a scene from Priyadarshan’s Boeing Boeing (itself an adaptation of a Western play/film), in which Jagathy Sreekumar is a writer trying to pitch a story (a variation on a story he’d pitched earlier): “I smoked cannabis before I wrote this. It’s the same old story, it just became like this when the style changed.” So it is, too, with Kili Poyi – the film’s style echoes back to classic comedies by directors such as Priyadarshan and Sathiyan Anthikad, only, in this case, filtered through a cannabis haze.

The interval of Kili Poyi is signalled by the song “Marijuana Virinju Vannal” from the Prem Nazir starring film Vijayanum Veeranum.

Contrast this to Aashiq Abu’s 2013 film Idukki Gold, the story of a group of middle-aged men. Michael (Prathap Pothen) is a Malayalee settled in the Czech Republic. Feeling the weight of responsibility of being a husband and a father, he longs for a time when, with his gang of school friends, they roamed the hills around Idukki. Michael decides to return to Kerala to find his old friends. He places an ad in a newspaper, hoping they will see it and get in touch with him. Ravi (Raveendran), now a photographer, and Madan (Maniyanpilla Raju), who is a planter, are the first to see the ad and connect with Michael. Together, they go off in search of the others. They find Antony (Babu Antony) in the restaurant he owns with his French wife (who is very much in control of both her husband and their restaurant) and Raman (Vijayaraghavan), who is on the verge of eloping with a work colleague.

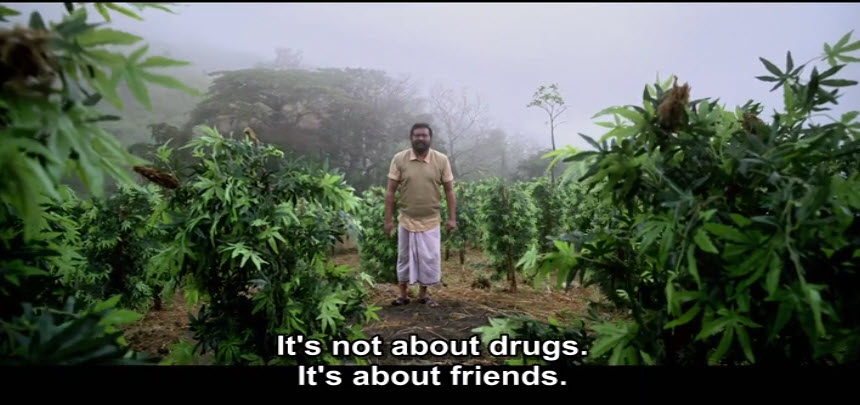

The film contrasts the lives of these middle-aged men – lives weighed down by responsibilities and disappointments – with their younger selves, the ones who chased girls and skipped classes and smoked beedis and the Idukki Gold of the film’s title. Idukki Gold is almost a kind of mythical strain of marijuana, once considered one of the finest strains in Asia, originally grown in Kerala and neighbouring Tamil Nadu, but its production declined with growth in population and increased police intervention in the region.

It strikes me that the film’s title is entirely used to highlight the past of these men – a past they remember as a time when they were most free – with their present, where they now have responsibilities and disappointments that weigh them down. Their return to Idukki to find the mythical Neela Chadayan (as the strain is also called, “Blue Locks” after the plant’s curly, blue tinged appearance) is a way for them to try to recapture a certain time in their lives, a time – like the Idukki Gold they remember smoking – that no longer exists, that has gone up in proverbial smoke. Time has a way of making us nostalgic, and that nostalgia colours the past, makes its hues rosier than the reality, and allows us to forget the parts of our past that were less than beautiful, pushes our sad memories into corners or makes them practically disappear. The five friends, fuelled by their hazy memories of Idukki Gold, discover in the end that you can never go back, and that there is little in the past that you can hang onto, apart from your friends. As the film’s closing message tells us: